Colossal Biosciences, the resurrectors of the direwolf, are opening up shop in Australia.

Once-extinct alpha predators prowl their old Tasmanian bushland haunts again. Others blithely munch on hapless cane toads without so much as a stomach-ache to show for it, thanks to a DNA tweak. The toads themselves are dwindling, along with other invasive pests - new genetics introduced into wild populations are curbing their breeding.

It's a future that's not quite here yet, but the shadow of it is looming, as one of the world's biggest names in de-extinction turns its eyes to Australia in a major way.

Colossal Biosciences, most famed for their projects to resurrect the woolly mammoth, and recreating the "dire wolves" made famous in Game of Thrones, have announced the establishment of Colossal Australia, expanding a long-standing partnership with the University of Melbourne.

READ MORE: Teen charged with murder over alleged underworld shooting

And joining the company full-time is Australian Professor Andrew Pask, who will step into the international role of chief biology officer, as well as overseeing Colossal Australia.

Pask said a greater focus on de-extinction in Australia, along with other environmental preservation techniques, was of particular importance.

"We have the highest rate of mammal extinction in the world," he told 9news.com.au.

READ MORE: New lab promises to curb algal bloom devastating state's seafood industry

Pask, a long-time leader in the de-extinction field, currently leads the Thylacine Integrated Genomic Restoration Research Lab (TIGGR) at the University of Melbourne.

Colossal has previously been a partial funder of the lab, but now, TIGGR will become part of Colossal Australia.

Among other things, it's at the heart of the company's plan to resurrect the thylacine - the Tasmanian tiger - which died out in 1936.

READ MORE: Victorian government announces complete overhaul of child safety practices

"We're currently in the (gene) editing phase for the Tasmanian tiger," Pask said.

He forecast it would be about six to eight years before that phase of the project was completed.

Concurrently, the lab is also developing breeding technology, from artificial wombs to ways to induce a "heat" phase in a prospective surrogate animal, which can be used for conservation projects around the country.

"We work with a lot of other organisations and we share a lot of our technology with them," Pask said.

Colossal is also working on a solution to the seemingly unstoppable menace of the cane toad, a species introduced to Australia in the 1930s.

Cane toads produce a toxin which is extremely poisonous and routinely kills animals who eat them, including native mammals and reptiles.

One of these would-be predators could soon have the upper hand.

The northern quoll was forecast to be extinct within 10 years, in part because too many are dying from eating toads.

Looking to the toad's native predators in South America for answers, Pask said they spotted a tiny difference in a single part of their DNA that could be mimicked by gene editing in Australian animals.

"One single nucleotide in a three-billion-letter DNA code, that's all you have to change," he said.

Colossal is currently working with regulatory bodies on the conditions of releasing the gene-modified quolls into the wild, which would be a world first.

"It hasn't been done before, so there's a lot to work through. With the gene change, the quolls are considered GMOs (genetically modified organisms), which means you can let them go but you can't eat them," he said.

Australia's Gene Technology Regulator offers licences for releasing GMO animals into the environment.

But there are other issues to work through - for example, as GMOs, the new quolls don't technically benefit from the environmental protections and conservation status of their natural-born cousins.

But Pask is optimistic.

"It's such a beautiful example of how we can use these de-extinction technologies to confront these issues," he said.

"The quolls aren't just protected from the toads, they're then helping getting rid of the pest animal."

Other project priorities for Colossal Australia include pushing ahead on bird genomics, which Pask said was "really far behind" compared to mammals, and which would have obvious applications for Australia's dwindling rare birds.

And Pask also suggested gene modification could be used to curb invasive pest species such as rabbits, by introducing animals that spread infertility genes.

"I'm thrilled to help lead this team at the forefront of de-extinction research, not just to bring back lost species, but to apply those technologies in real-time to save those still with us," he said.

DOWNLOAD THE 9NEWS APP: Stay across all the latest in breaking news, sport, politics and the weather via our news app and get notifications sent straight to your smartphone. Available on the Apple App Store and Google Play.

Australia directly in the firing line of 'catastrophic' shift

Australia directly in the firing line of 'catastrophic' shift

Father and son missing after car hit tree and crashed into NSW river

Father and son missing after car hit tree and crashed into NSW river

Man and dog pulled to safety in daring flood rescue

Man and dog pulled to safety in daring flood rescue

Trump once railed against TikTok. Now the White House has an account

Trump once railed against TikTok. Now the White House has an account

Israeli army's plan for Gaza occupation facing big manpower problem

Israeli army's plan for Gaza occupation facing big manpower problem

Two teens charged after second shopping centre stabbing

Two teens charged after second shopping centre stabbing

Bruce Lehrmann lied on stand to conceal rape, court told

Bruce Lehrmann lied on stand to conceal rape, court told

Man throws hammer at woman's car in road rage incident in Melbourne

Man throws hammer at woman's car in road rage incident in Melbourne

French streamer dies live online during extreme challenge

French streamer dies live online during extreme challenge

Part of US plane's wing breaks off during flight

Part of US plane's wing breaks off during flight

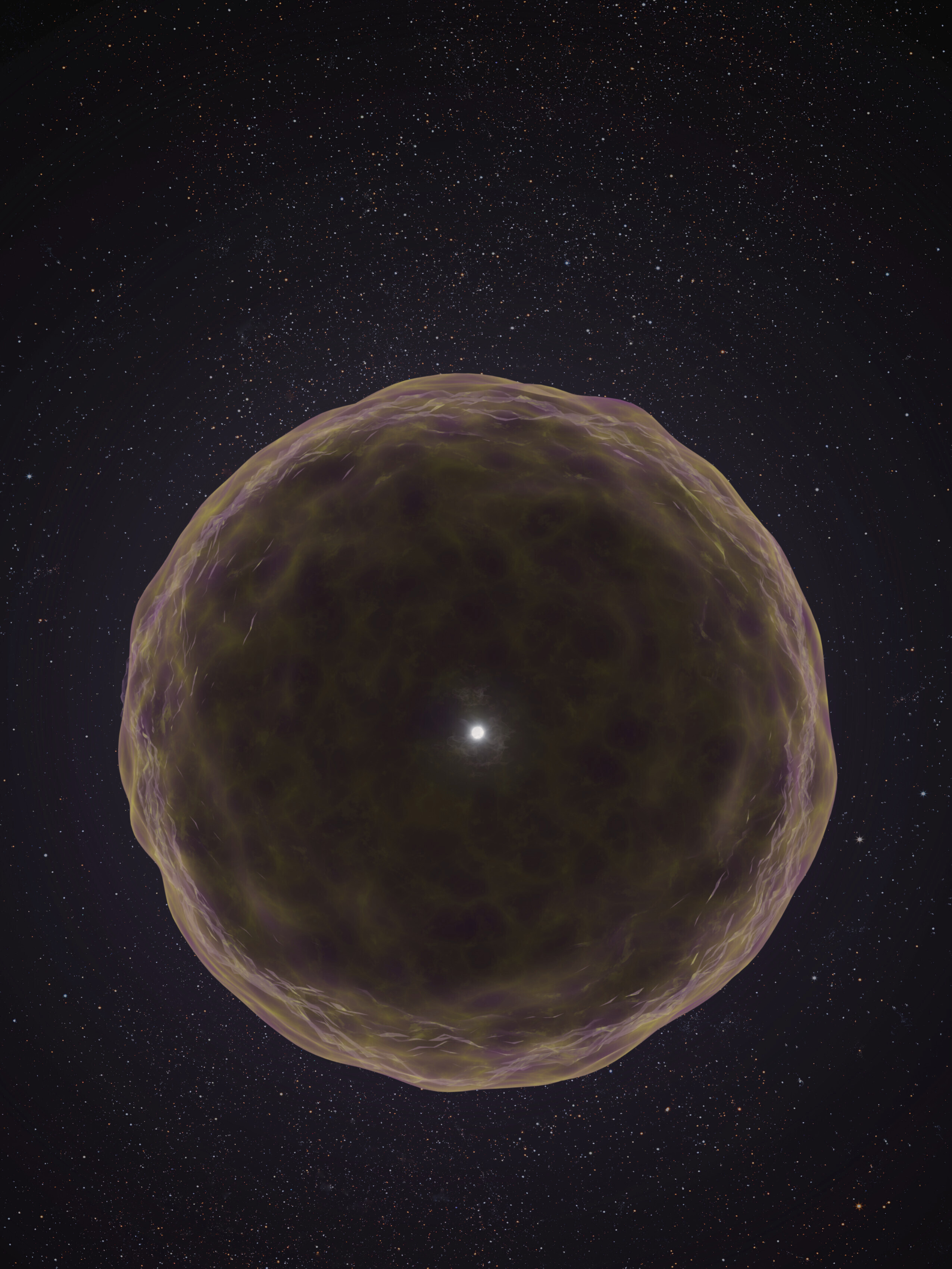

Scientists get a rare peek inside of an exploding star

Scientists get a rare peek inside of an exploding star

Has your data been leaked? It could be waiting for the highest bidder on the dark web

Has your data been leaked? It could be waiting for the highest bidder on the dark web

Childcare centres failing to meet national standards named and shamed

Childcare centres failing to meet national standards named and shamed

New Call of Duty game revealed

New Call of Duty game revealed

Reality TV star offered $10,000 to injured pilot's family, court hears

Reality TV star offered $10,000 to injured pilot's family, court hears

Perth doctor pleads guilty over drunken high-speed crash that killed young woman

Perth doctor pleads guilty over drunken high-speed crash that killed young woman